Boston Massacre

Boston Massacre, Boston, MA

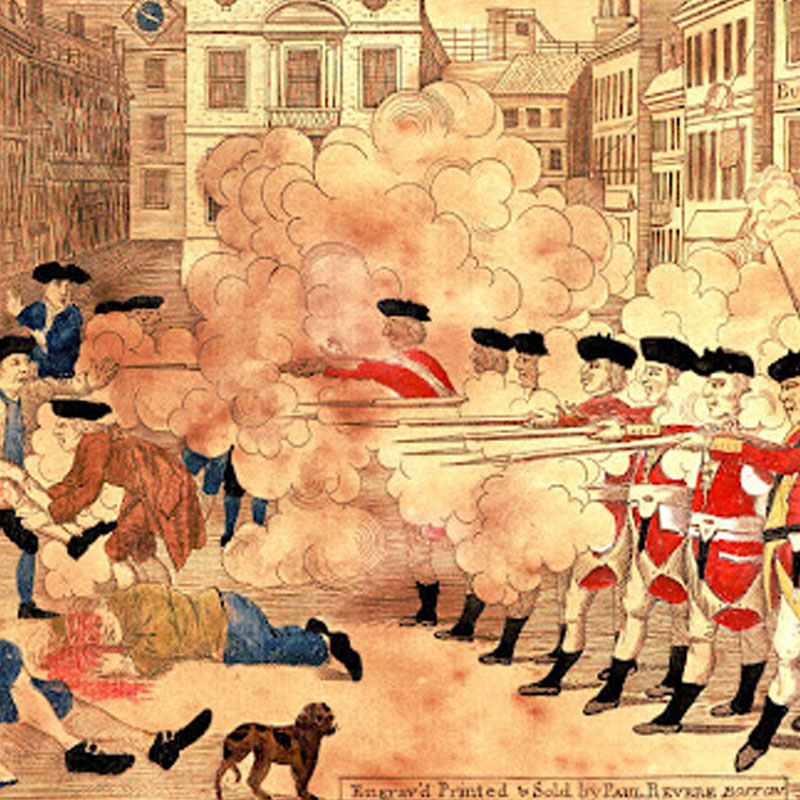

March 5, 2020 is the 250th Anniversary of the Boston Massacre. On March 5, 1770, there was a great deal of unrest throughout the town of Boston. Roving gangs of Bostonians vented their frustrations on unsuspecting soldiers and officers belonging to the 14th and the 29th Regiments of Foot. A group of young Bostonians surrounded a sentry at the Customs House on King Street (now State Street). The sentry felt threatened by the crowd because they were hurling pieces of ice, snow and other street detritus along with volleys of invective and abuse. Local citizens reported the plight of the sentry to the Main Guard, a reserve force of British soldiers stationed near the State House. Captain Thomas Preston of the 29th Regiment was Officer of the Day and he led a reserve force of 12 to the aid of the Custom House sentry. Events spiraled out of control resulting in the soldiers firing on the crowd, immediately killing Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray and James Caldwell, mortally wounding Patrick Carr and Samuel Maverick. Edward Paine and Christopher Monk were among the wounded. Monk would die several years later as a result of his wounds.

Printed Accounts

- A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England

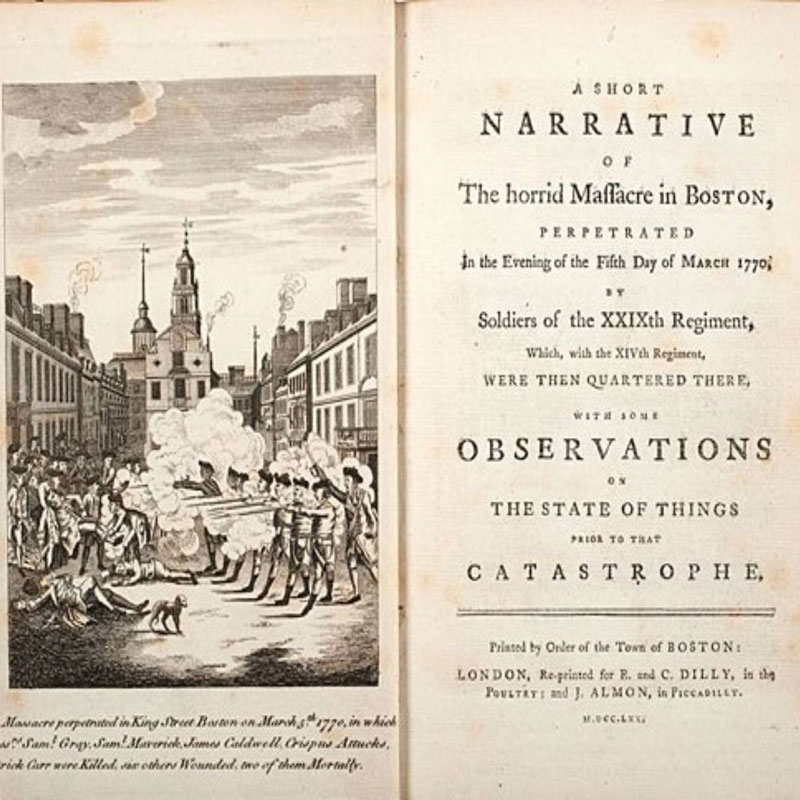

- A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston

- Additional Observations on a Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre

- 1870 History of the Boston Massacre by Frederic Kidder

Manuscript Text

- Samuel P. Savage Diary February & March 1770

- Samuel P. Savage Long Diary; 1 – 10 March 1770

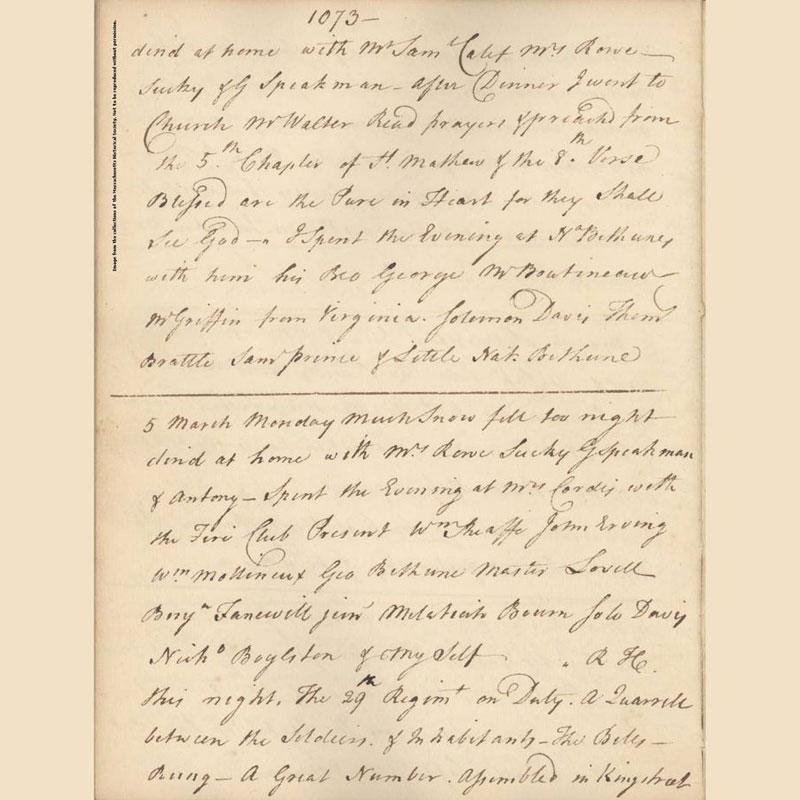

- John Rowe diary 7, 5-6 March 1770, pages 1073, 1076-1077

- David Hall diary 2, 11-25 March 1770

- Deposition of Joseph Belknap regarding 5 March 1770, manuscript copy by Jeremy Belknap, 1770

- Letter (copy) from a Committee of Boston selectmen to Benjamin Franklin, 13 July 1770

- Letter from Andrew Oliver, Jr. to Benjamin Lynde, 6-7 March 1770

- Letter from William Molineux to Robert Treat Paine, 9 March 1770

- Letter from Gregory Townsend to Jonathan Townsend, 15 March 1770

- Letter from James Bowdoin, Samuel Pemberton and Joseph Warren to Dennys De Berdt, 23 March 1770

- Letter from Thomas Gage to Thomas Hutchinson, 30 April 1770

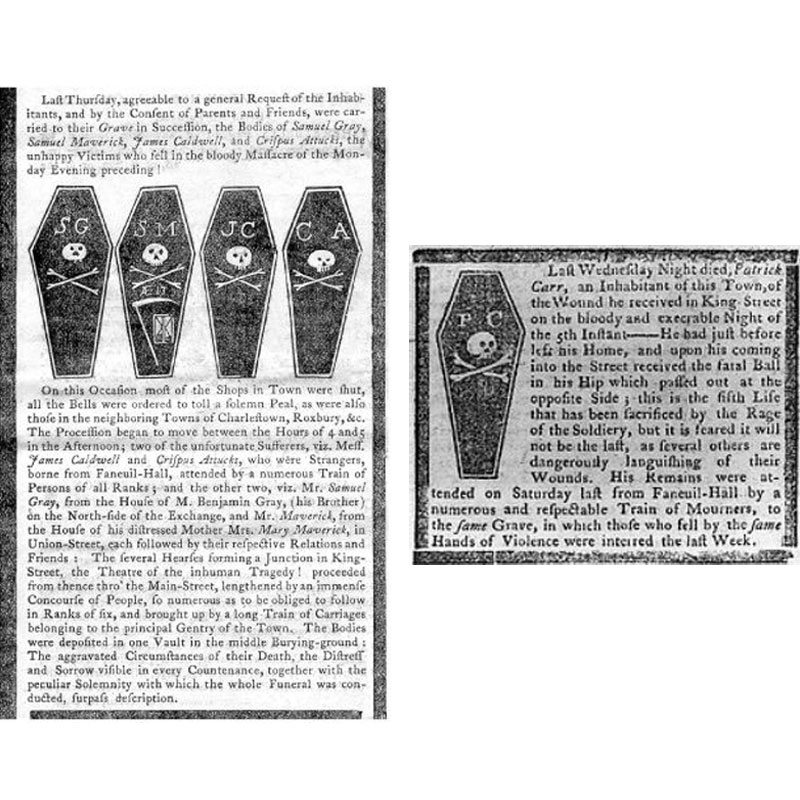

The Funeral of the Massacre Victims

I have Reason to remember that fatal Night. The Part I took in Defence of Captn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right. – Diary of John Adams, 5th March 1773

On the 6th of March 1770, the day after the “Affair on King Street,” also known as the Boston Massacre, Captain Thomas Preston, a 48-year-old captain in the 29th Regiment of Foot and 8 of his men as well as 4 civilians were all conducted to the town jail where they were to await indictment for the murders of Crispus Attucks, Samuel Maverick, Samuel Gray, Patrick Carr and James Caldwell. The soldiers of the twenty-ninth regiment accused of murder were William Wemms, James Hartigan, William McCauley, Hugh White, Matthew Kilroy, William Warren, John Carrol and Hugh Montgomery.

Facing a capital charge that carried a sentence of death, Captain Preston set out to find legal representation for himself and his men. As expected, there was great difficulty in finding an attorney who would take on the case, but James Forrest, an Irish-born merchant in Boston eventually succeeded in getting Josiah Quincy to agree to take the case. Josiah Quincy had already been approached by the leading men of Boston to take the case in an effort to show that the soldier’s would get a fair trial.

It was also Forrest who engaged John Adams in the case. Completing the team were Sampson Salter Blowers, a young lawyer in the office of John Adams, and Robert Auchmuty, a judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court.

The counsel for the prosecution was headed by Samuel Quincy, Josiah Quincy’s older brother. He recruited Robert Treat Paine, a prosperous attorney in Southern Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

A decision was made to sever the trials of Captain Preston and that of his men, although several of his men argued against the severance. However, the defense could not risk the cross-arguments for the various defendants. Did the soldiers fire because Preston told them to, or did they fire ignoring their commanding officer?

The soldiers’ trial started November 27th and lasted until December 5th.

The defense of the soldiers was complicated by the acquittal of Thomas Preston since the jurors would be inclined to believe the soldiers were responsible for the shootings. As a result the defense focused on the actions of the mob that threatened the soldiers in order to pursue a justifiable use of force in self defense. Adams argued that if the soldiers were attacked by “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jacktars,” At most, Adams argued, the soldiers were guilty of manslaughter and not of murder.

An important circumstance in the trial was the death bed testimony of Patrick Carr. Carr had been wounded on March 5th, and before he died he admitted to his physician, John Jeffries, that the soldiers were provoked and fired in self defense and that he (Patrick Carr) did not blame the soldier who shot him.

The prosecution concentrated on showing that soldiers wanted revenge after many months of being abused and harassed by townspeople. A witness testified that Private Killroy had admitted to him that “he would not miss an opportunity to fire on inhabitants”. However, the prosecution’s case was undermined on cross-examination when witnesses admitted that the crowd was throwing objects and provoking the soldiers to fire.

In his summation, Adams famously argues:

I will enlarge no more on the evidence, but submit it to you.—Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter, in consideration of those passions in our nature, which cannot be eradicated. To your candour and justice I submit the prisoners and their cause.

The jury acquitted six of the soldiers: William Wemms, William M’Cauley, Hugh White, William Warren, John Carrol and James Hartegan. The other two soldiers, Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Killroy, were found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter, therefore escaping the death penalty. Both men invoked the “benefit of the clergy” allowing them to avoid a long imprisonment. They had their thumbs branded with the letter “M”, leaving a permanent mark so that they would not receive a lenient treatment in the future.

On December 13th, the four civilians who were accused of firing from the customs house were tried. All four were acquitted as the only prosecution witness presented a false testimony. The witness was later convicted of perjury.

The trials did not take place immediately. Thomas Gage, the commander of British troops in America, urged Thomas Hutchinson to delay the trials until feelings against the soldiers had cooled. Seven months passed between the Boston Massacre and the start of the trials on October 24, 1770. During this time a propaganda war broke out trying to seize upon the hearts and minds of the public and affecting public opinion in the colony as well as in the mother country.

The town of Boston appointed a committee that included James Bowdoin, Joseph Warren and Samuel Pemberton who were in charge of submitting an official account of the Boston Massacre entitled “A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston”. In addition to a rambling narrative it contained an appendix of 95 depositions that told the Town’s side of the story. (But only about one-third of the deponents testified at any of the ensuing trials.) Perhaps the most influential propaganda was Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre which contained inflammatory details such as Captain Preston ordering his men to fire and the customs office shown as “Butcher’s Hall.

Thomas Preston’s trial took place from October 24th to the 30th, 1770 in Boston’s new courthouse, just a few dozen yards from the site of the massacre. A six-day trial was unusual in Massachusetts. Preston pleaded not guilty but did not testify. (Defendants did not testify in their own behalf back then.) The defense argued that Preston had not ordered the shooting. The prosecution called fifteen witnesses to but on cross-examination their testimony appeared contradictory. The defense produced twenty-three witnesses who testified that soldiers were intimidated and provoked by the crowd. Much of the cross-examination by the defense was centered on who shouted the word “fire”.

The court took the unusual step of sequestering the jury (keep them away from family and friends) in the town jail. After much deliberation the jury acquitted Preston on the basis of “reasonable doubt.”.

Primary Sources

- Judge Peter Oliver’s Notes on the Trial of William Wemms, et al.

- Boston Massacre Trial Notes of John Adams held by the BPL

- John Rowe diary 8, 1770-1771, pages 1187-1191

- John Rowe diary 8, 1770-1771, page 1210

- Notes on the Boston Massacre trials, by John Adams, 1770, “Captn. Prestons Case”

- Minutes of Robert Treat Paine’s argument, by unidentified note taker, 29 October 1770

- Notes on the Boston Massacre trial relating to the trial of the eight soldiers, by Benjamin Lynde, circa November 1770, “If therefore on ye whole of ye Evidnce …”

- Notes on the Boston Massacre trial relating to the trial of the eight soldiers, by Benjamin Lynde, circa November 1770, “No. 1 Je Hartagun Wm Mcauley…”

- Notes at the trial of British soldiers, circa November 1770, by Samuel Quincy

- Notes on the Boston Massacre trials, by John Adams, 1770, “Prisoners Witnesses. James Crawford…”

- Notes on the Boston Massacre trials, by John Adams, 1770, “seemed to come from close before them…”

- Memorandum from Samuel Adams to Robert Treat Paine, [29 November 1770]

Boston Massacre Orations

On March 5, 1771, one year to the day following the Boston Massacre, the Town Fathers of the Town of Boston decided that there needed to be a public oration to remember the event.

Dr. Thomas Young

(1731 – 1777)

No copy of Doctor Young’s address has yet been discovered.

An avowed Deist from Connecticut, Dr. Young moved to Boston in 1765. Dr. Thomas Young was a member of the Committee for Correspondence in 1772. In 1774, Young left Boston for Newport and eventually moved on to Philadelphia where he aided in the drafting of the Pennsylvania State Constitution. As a physician, he served the American army as surgeon.

James Lovell

(1737 – 1814)

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/3/sequence/1038

Born in Boston on the 31st of October 1737, Master James Lovell entered Latin school in 1744 and graduated from Harvard in 1756. Lovell served as usher in the Latin School, of which his father was Master until the battles of Lexington & Concord in 1775. Lovell was arrested and thrown into jail by General William Howe who found letters on the body of General Joseph Warren implicating Lovell in working against the British army. Lovell continued in the custody of the British army even after they removed to Halifax, NS. He was finally exchanged for Colonel Skene of Ticonderoga in November of 1776. In December of 1776 he was elected as a representative to the Continental Congress, and he served in several early Federal offices such as Collector of Taxes and Collector of the Port of Boston until his death.

Dr. Joseph Warren

(1741 – 1775)

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/4/sequence/1162

Dr. Warren was born the 11th of June 1741 in Roxbury, Massachusetts the son of a farmer. He attended Roxbury Latin School and graduated from Harvard College in 1759. An ardent Son of Liberty he was strongly associated with the Patriot cause. He performed the autopsy on Christopher Seider, the boy killed by Ebenezer Richardson who fired a gun filled with swan shot out his window at a group of protesting boys. Dr. Warren was a Master Mason who authored the song “Free America” in 1774. Warren was appointed President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and drafted the Suffolk County Resolves. He was killed in the redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The identification of his body following the evacuation of the British was done using dental work performed on him by Paul Revere.

Dr. Benjamin Church

(1734 – 1778)

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/4/sequence/1220

Dr. Church was born in Newport, RI on 24 August 1734. He attended Latin School and Harvard (1754). He went to England where he trained in the London Medical College. Dr. Church performed the autopsy on Crispus Attucks and was a deponent in the trial. In October of 1775, Dr. Church was convicted by a court-martial of holding criminal correspondence with the enemy and expelled from camp. A further examination of the House of Representatives condemned Church and the Continental Congress desired him to be imprisoned in Connecticut. Dr. Church was released from jail in May of 1776 and returned to Massachusetts where he was imprisoned until 1778 when he was banished under the Massachusetts Banishment Act. It was said to sail for London, or Martinique, but he was never heard from again.

John Hancock

(1737 – 1793)

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/4/sequence/1280

John Hancock was born in Braintree on January 23, 1737 in Braintree, Massachusetts. When John was 7 years old, his father passed away, prompting the family to place him in the care of his uncle, Thomas Hancock and his wife Lydia. John attended Latin School and Harvard College (1754) and he was trained up in his uncle’s import and export business. He would eventually inherit the Hancock mercantile business, as well as the large and well-appointed house on Beacon Hill. Despite his wealth, Hancock played an important role in the lead up to American Independence and held several important public offices, including the Presidency of the Second Continental Congress, during which he famously affixed a large signature to the Declaration of Independence. He served as commander of the Massachusetts militia and was active in the naval forces of the American Revolution, raising money to build and outfit cruisers and frigates for the nascent American navy. After the Revolution, he served several terms as Governor of Massachusetts.

Peter Thacher

(1752 – 1802)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Reverend Peter Thacher was born in Milton, Massachusetts on the 21st of March 1752. He entered Latin School in 1763 and graduated from Harvard College in the class of 1769. He was active in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and wrote, at their request, a narrative of the Battle of Bunker Hill. He served as minister of the Brattle Street Church and was a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society. After the Revolution, Rev. Thacher was frequently Chaplain of the Massachusetts Legislature.

Benjamin Hichborn

(1746 – 1817)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Benjamin Hichborn was born in Boston on the 24th of February 1746 and was a graduate of Harvard College (1768). An eminent lawyer, he was an early supporter of the cause for independence, a fact which saw him serve time as a captive onboard a British man of war in 1775. He served as Colonel of the Corps of Cadets and marched with them to Rhode Island in 1778.

Jonathan W. Austin

(1751 – 1779)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Jonathan Austin was born at Boston, April 18, 1751 and was a graduate of both Boston Latin School and Harvard College (1769). Austin studied law with John Adams and was a sworn witness at the trial of the soldiers of the 29th Regiment in 1770. He was admitted to the bar in Suffolk county and died in the service of America.

William Tudor

(1750 – 1819)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

William Tudor was born in Boston 28 March 1750 and entered the Latin School in 1758. Tudor graduated from Harvard College in 1769 and served as Judge Advocate General in General Washington’s army with the rank of Colonel. Tudor also hosted the organizing meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Tudor was one of John Adams law clerks in the early 1770s.

Jonathan Mason

(1752 – 1831)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Jonathan Mason was born in Boston 30 August 1752; entered Latin School in 1763 and graduated from Princeton College in 1774. Mason was one of the deponents of the Boston Massacre. He served in both the U.S. House of Representatives & the U.S. Senate.

Thomas Dawes

(1758 – 1825)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Thomas Dawes was born in Boston on July 8, 1758. He entered Latin School in 1766 and graduated from Harvard College in 1777. Dawes served in numerous judicial capacities including judge of Probate of Suffolk County and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts.

George R. Minot

(1758 – 1802)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

George Minot was born in Boston on 22 December 1758. He entered the Latin School in 1767 and graduated from at Harvard College in 1778. He served in numerous judicial posts, including judge of Probate and judge of the Boston Municipal Court. He was an early member of the Massachusetts Historical Society and edited the first 3 volumes of the Massachusetts Historical Collections. He also published a continuation of Thomas Hutchinson’s History of Massachusetts, a History of the Insurrection in Massachusetts and several other works.

Thomas Welsh

(1754 – 1831)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009588849

Thomas Welsh was born at Charlestown June 1, 1754 and was an army surgeon at Lexington and at the battle of Bunker Hill. Dr. Welsh later served as surgeon on Castle Island. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and Vice President of the Massachusetts Medical Society.